Skip to content

Full replay of 2 May webinar with Q&A

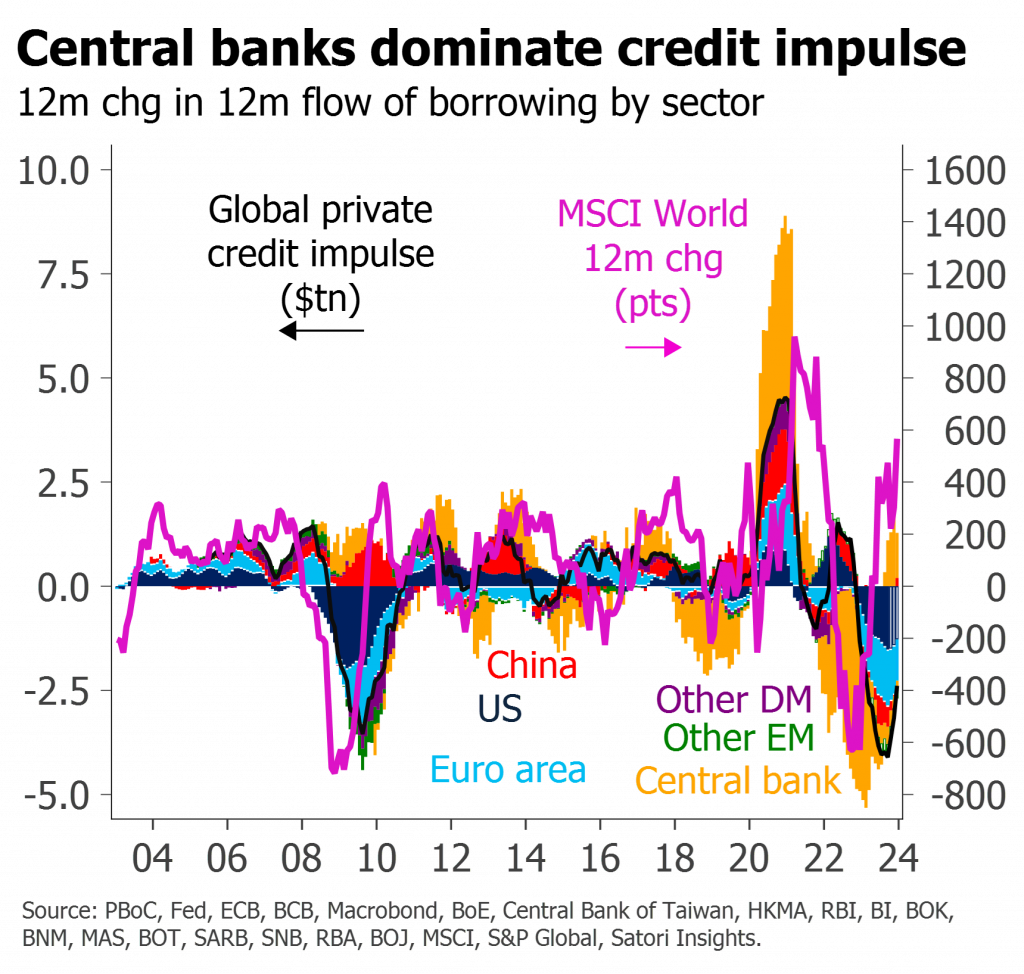

The exuberance in risk assets is less a consequence of a stronger economy than a driver of it

The expectation of rate easing was never critical – which is why the exuberance has largely persisted even as yields have backed up

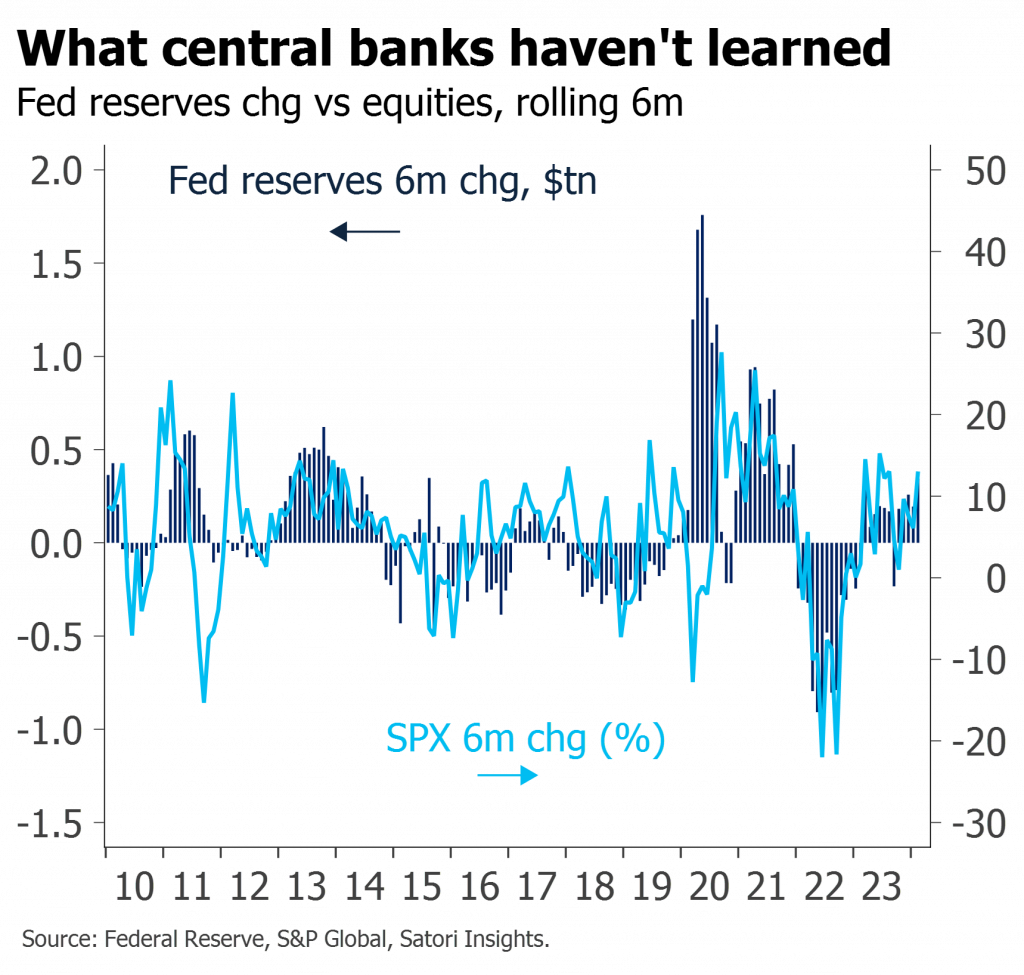

It is instead the direct consequence of investor crowding following easy central bank balance sheet policy – and vulnerable to any reduction in CB liquidity

Open to clients with Group Webinar or One-on-One subscriptions, and to the press

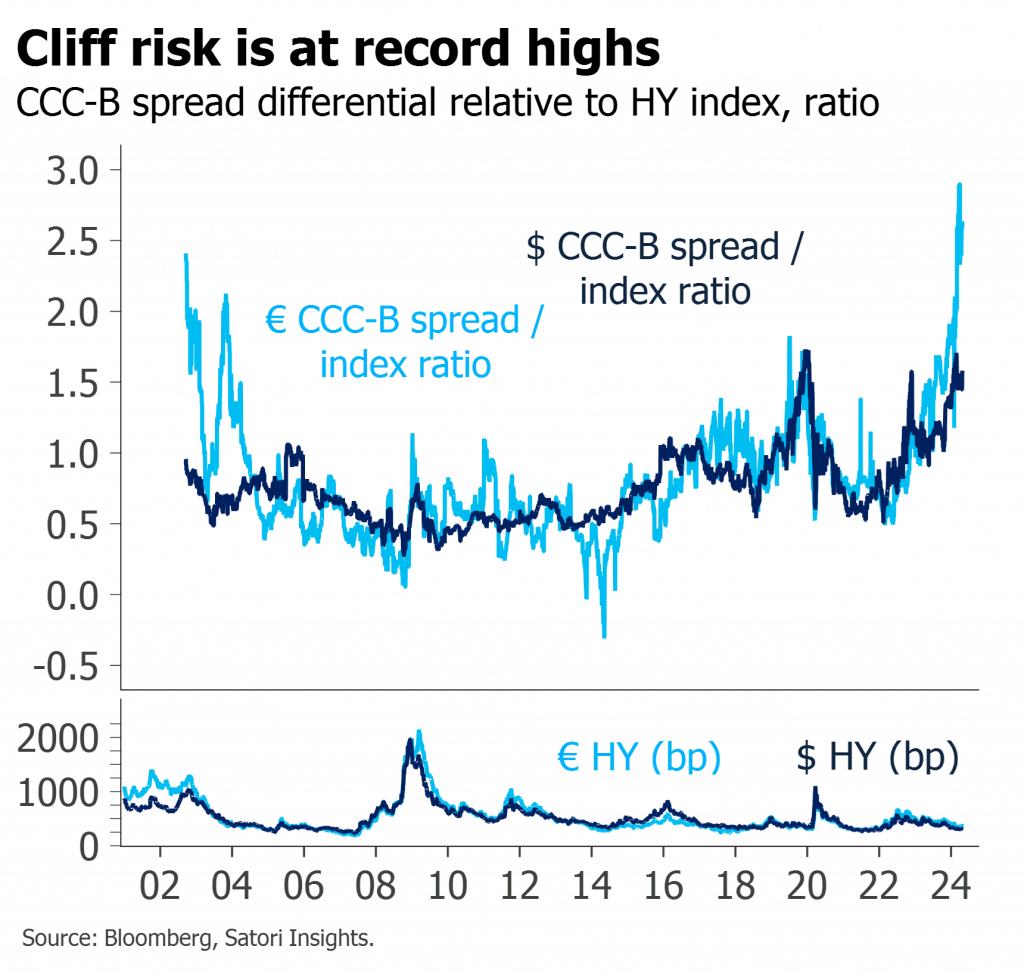

Relative CCC cliff risk has risen to record highs

This partly reflects hidden idiosyncratic risks from low recoveries and abandoned covenants

But mostly it signifies the macro suppression of index spreads

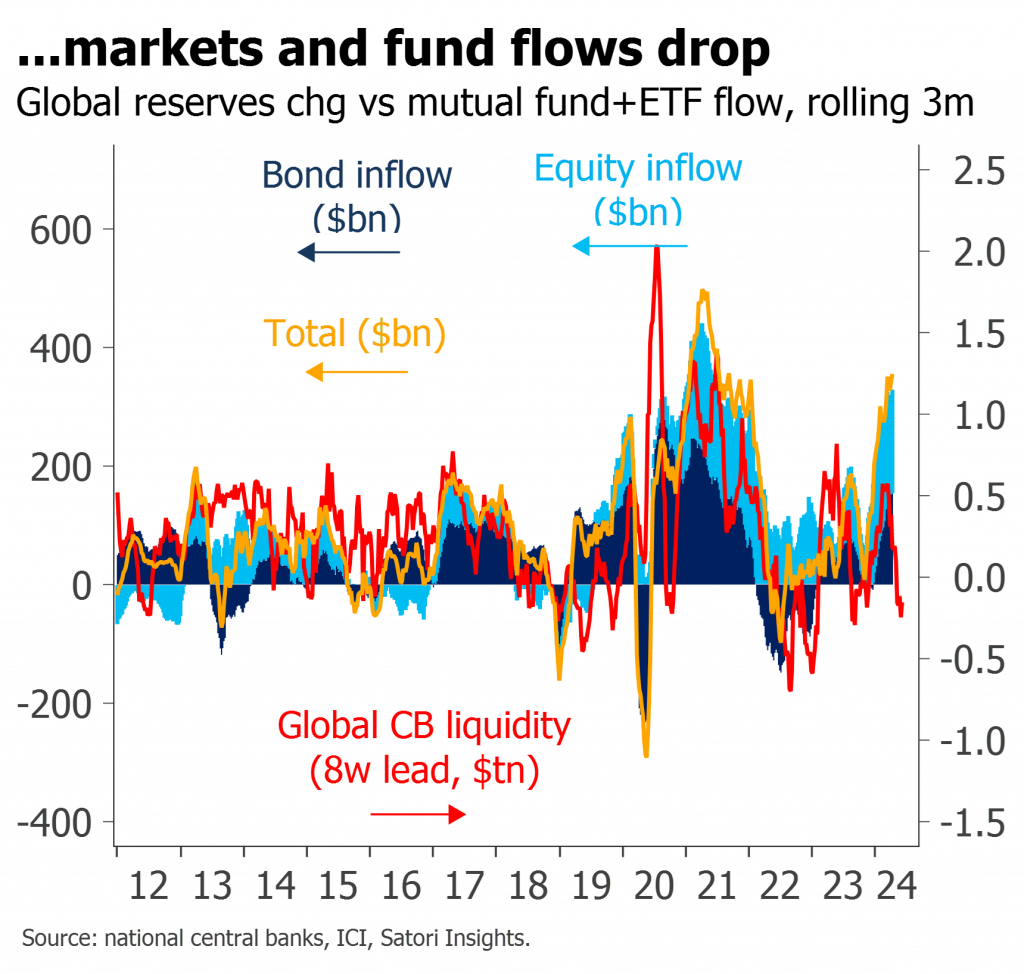

The $280bn weekly drop in Fed reserves is the largest since Apr22

Just as then, it coincides with a correction in markets

A drop in fund inflows seems likely to follow

But this still feels more like seasonal correction than decisive turn

Financial conditions have eased to the same levels as 2007

This comes in spite of central banks thinking they are running restrictive policy

The nature and timing of the market moves suggest these not so much reflect or anticipate the strength of the economy as drive it

Their ultimate cause is easy balance sheet policy having crowded investors into risk

Misunderstanding of these dynamics increases the likelihood of bubbles and subsequent busts

The latest central bank research on QT is careful, rigorous, and grounded in the literature

Unfortunately its main conclusion – that QE affects markets while QT doesn’t – is at odds with the lived experience of most market participants

There is a much simpler reason why QT has had so little apparent impact

Misunderstanding of this dynamic greatly contributes to the likelihood of future policy mistakes

The rally in risk is often attributed to strong earnings

But calendar earnings estimates have mostly been falling

Macro drivers, not organic estimate optimism, are the true source of the markets’ strength

After several months of liquidity tailwinds, risk asset pricing is starting to look excessive

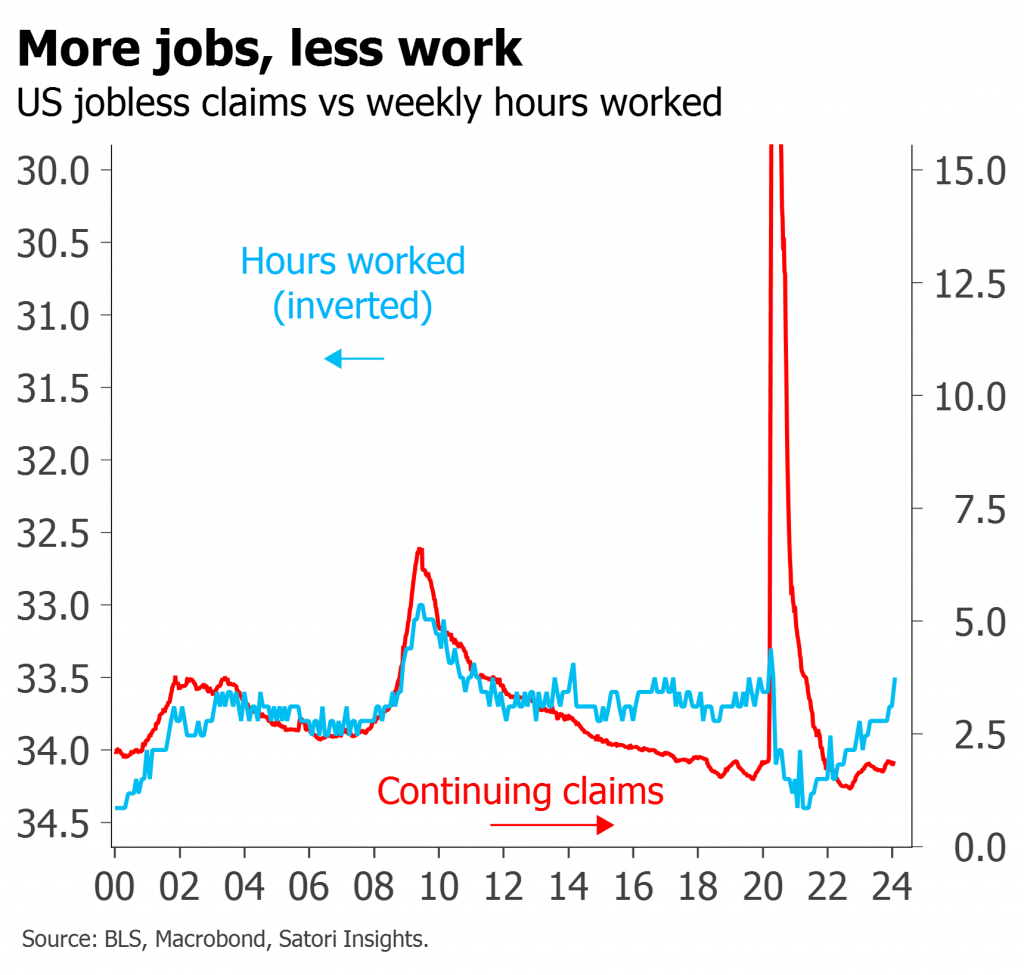

Improving spending, orders and hiring are all positives

Despite this, earnings estimates are falling

Fundamentals are reflective more of sticky supply than of dynamic demand

Ongoing price pressures may well curtail central banks’ desire for dovishness

But excitement about higher r* remains overdone

Free-to-view replay of first segment of 16 Jan webinar

Why strategists struggled in 2023

A better way to think about markets

Implications for 2024

Full replay from 16 Jan webinar with Q&A

Why strategists struggled in 2023

A better way to think about markets

Implications for 2024

Open to clients with Group Webinar or One-on-One subscriptions, and to the press

The remarkable performance of risk assets in 2023 is not primarily due to the growing likelihood of a soft landing

It instead reflects markets being buffeted by extraordinary amounts of central bank liquidity

For now, those technicals remain positive, but beyond Q1 they should fade or reverse

Underlying momentum in growth, earnings and inflation – beyond sticky supply-side effects – is significantly weaker